11 Case Interview Frameworks (and How to Use Them Effectively)

You’re staring at a slide. A company’s profits are dropping:

- Maybe they want to enter a new market.

- Maybe their prices are all over the place.

- But…you don’t know the numbers, the market is unfamiliar, and the interviewer is watching quietly.

Your mind races. What should you say?

For many candidates, the first instinct is to panic and throw out quite random guesses. Or maybe list every possible factor, with the hope that something works.

Unfortunately, that rarely works.

What separates a candidate who stumbles from one who actually does well on these interviews is business frameworks.

And yet, these structures only work if you adapt them.

The worst mistake candidates make is pulling out a profitability framework or a market sizing case framework and applying it without thinking:

- Every case is different.

- Every particular market has its own dynamics.

- And if you blindly follow a rigid structure, you’ll miss opportunities to show true insight.

In this article, we’ll go through the most common consulting frameworks and show how to use them to answer tough questions effectively.

What is a case interview framework?

Essentially, a case interview framework is just a way to organize your thinking.

- It’s not a magic formula.

- It’s not a guaranteed answer.

- It’s not something you can just memorize and reiterate.

It is a structure that helps you break a newly faced problem into pieces you can deal with logically.

Here's a typical case:

- A company is considering a market entry into a new region.

- The interviewer doesn’t hand you a neat spreadsheet with all the data upfront.

- You are the one who needs to decide what matters most: the size of the target market, the competitive landscape, or internal capabilities.

And a market entry template gives you a way to consider all of these systematically without forgetting anything important.

Why use it?

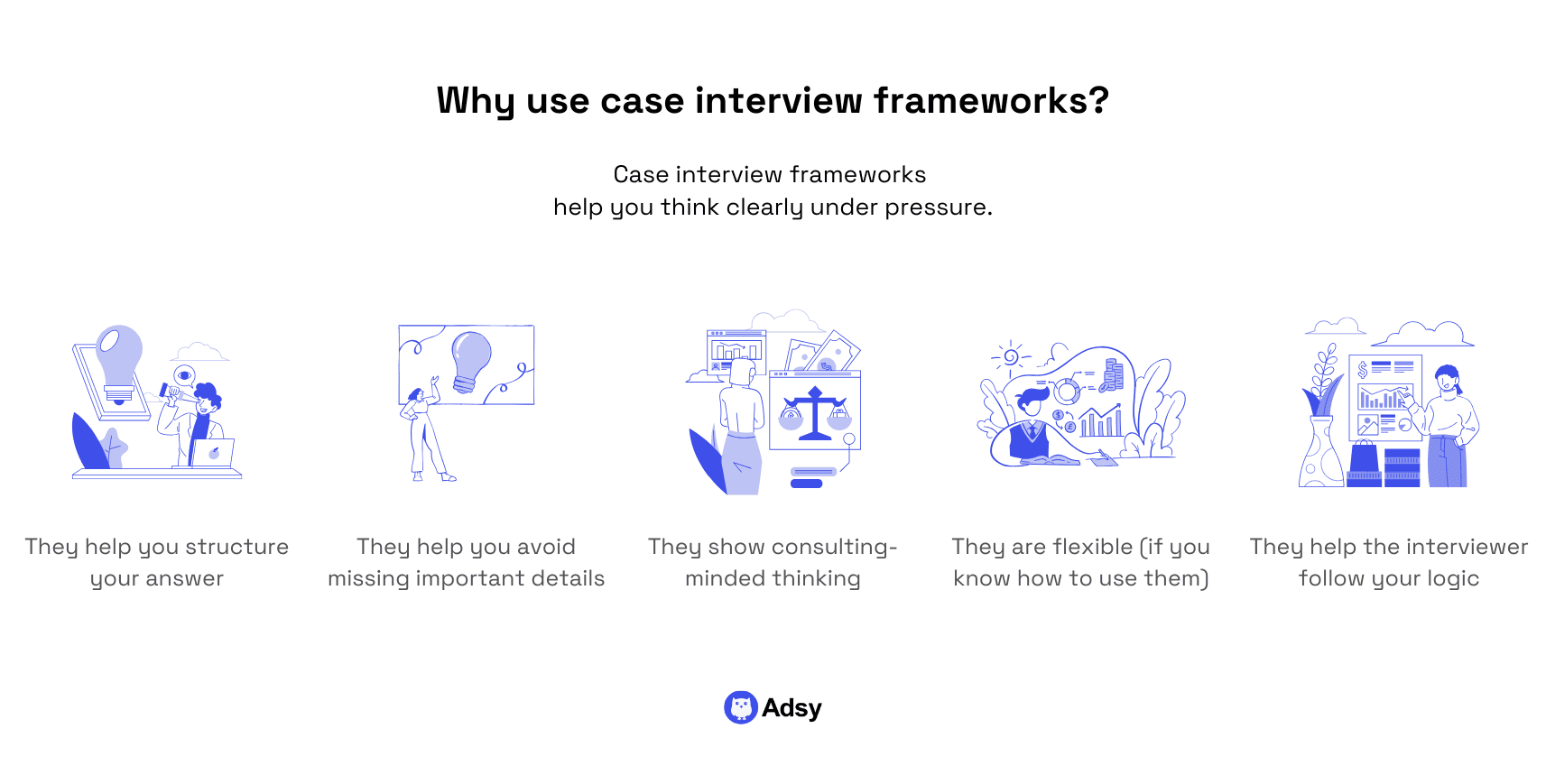

Here’s why case interview frameworks matter:

1. They help you structure your answer

Interviewers want to see how you think.

A proper case interview template shows you can dissect a problem logically and bring structure to something unstructured.

2. They make sure you don’t miss important details

Case-solving templates reduce the chance of you forgetting a key analysis area. Of course, it only works if you adapt them to the case.

As such, they do not guarantee completeness.

But when adapted correctly, they can help you cover the major aspects of the case systematically instead of guessing or jumping around.

3. They show consulting-minded thinking

Using consulting frameworks demonstrates that you understand how profitable businesses analyze situations in the real world.

Sure, consulting firms typically don’t require you to name any model. But they want to see your structured and logical thinking.

And that’s where a clear methodology can help.

4. They are flexible

That's probably the most advantageous thing you have. You can adapt a case interview structure as you go.

Any operation is okay: adding, removing, or emphasizing parts depending on the data the interviewer gives you.

And that’s what interviewers tend to value most.

5. They give the interviewer a mental map of where your analysis is going

That alone makes a huge difference. When your structure is clear, even imperfect ideas land better, and interviewers assess you better.

Even if your analysis is incomplete, clarity and structure score points.

A good candidate adjusts the structure in real time. Because in the real world, you have to reshape some parts of any template to match the client’s actual problem.

Sometimes, that means really tweaking ideas:

- A pricing framework might need a touch of Porter’s Five Forces if the interviewer mentions aggressive competitors.

- A market entry framework might require a deeper dive into distribution channels if the region has fragmented logistics.

Essentially, you have to move your case analysis models out of the “template” category and into the “thinking tool” category.

Why do they often fail you?

If frameworks are so useful, why do so many candidates still crash and burn when they use them?

There is a good reason for that. Actually, there are quite a few reasons…

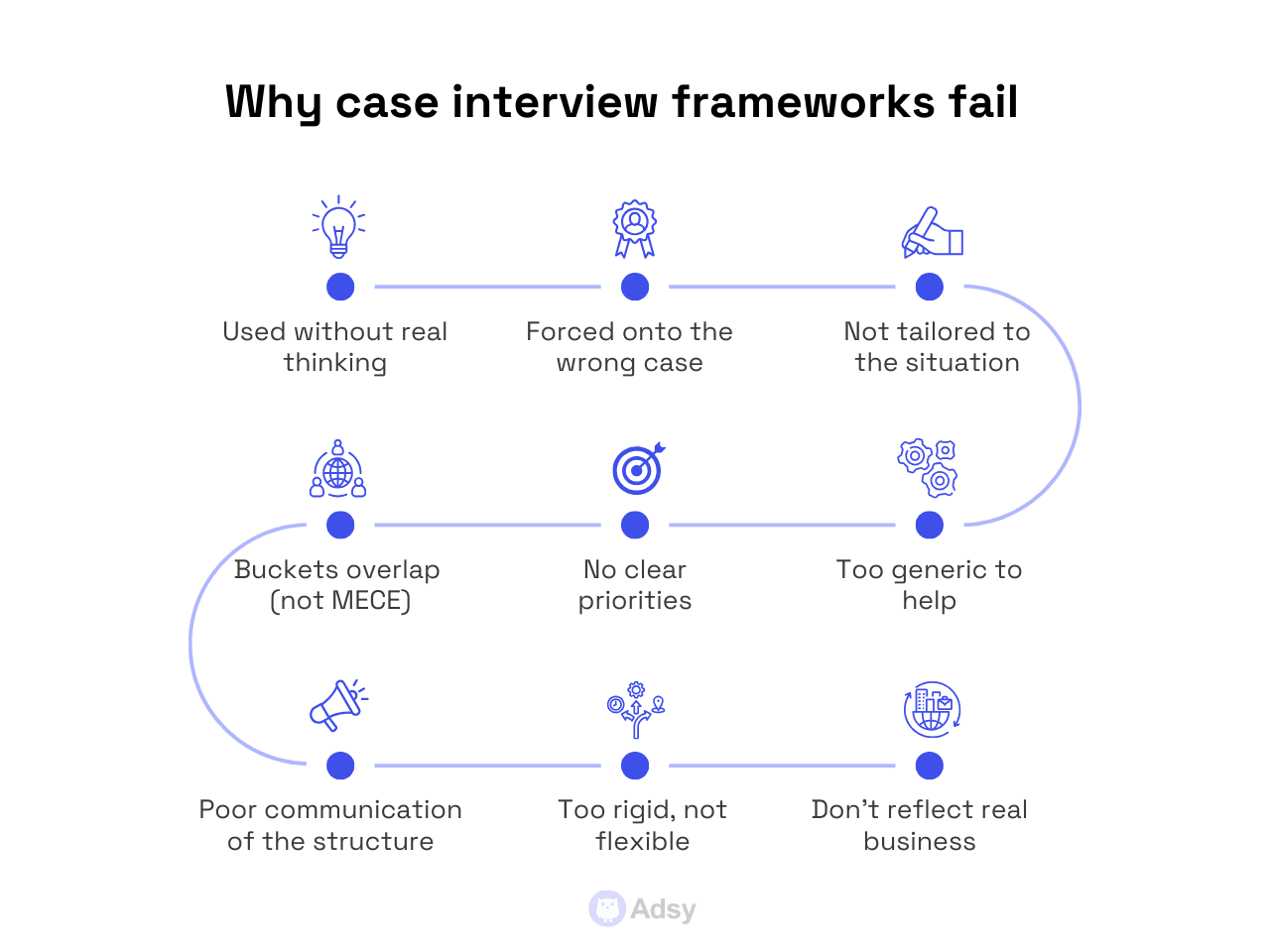

They’re misused

Sure, a structure is supposed to help you think. But it can’t replace thinking, no matter what you do.

Still, many candidates use it like a shield, like something to hide behind when they’re unsure.

You’ve probably seen this:

Someone gets a profitability question and immediately jumps to revenue and costs. Even when the interviewer hinted that the issue is not that much financial, but rather operational.

When a framework becomes a reflex and not a tool (as it is supposed to be), it stops helping.

Interviewers don’t want to see a “template rehearsal.” They want to see that you understand the problem in front of you. That you can think, reason, and be logical.

Misuse happens when the framework drives your answer. In reality, your understanding should drive any structure instead.

They’re forced into cases that don’t fit

This is the framework equivalent of forcing a puzzle piece where it doesn’t belong.

These are some typical examples. Imagine:

- You get a supply chain case … and right away use a market entry structure.

- You get a product cannibalization question … and choose Porter’s 5 Forces immediately.

Interviewers know when you’re doing this in just a second. It tells them you’re relying on memorization when they actually expect you to do a real analysis.

But the rule you have to apply is simple.

If the case doesn’t naturally fit into any model, don’t force it.

Frameworks are meant to support your reasoning. When you twist the case to fit the structure, you show the opposite of business intuition.

They aren’t adapted to the case realities

You can take the best template in the world and still fail. If... you don’t adapt it.

Here are just a few examples when correction is needed:

- A market entry in a highly regulated industry? It is a good idea to add a section on regulatory constraints.

- A pricing case for a SaaS product? You need to adjust for churn, acquisition cost, and customer lifetime value.

- A profitability decline caused by internal politics or flawed incentives? Well, you won’t see either of those in the classic profitability structure.

Many candidates think “adaptation” means adding an extra bullet to already memorized approaches. But it is slightly more complicated than that.

Adapting means reshaping your structure to match the client’s reality.

Too generic to be useful

“Let’s look at the market, the company, the competition, and the customer.”

Congratulations, you’ve said nothing useful or impressive in the slightest. That's not even an offer to start from a marketing audit.

Generic frameworks fail for one simple reason: they’re vague.

They don’t help you think, and they don’t tell the interviewer anything about where you’re going.

When you say “Let’s look at the company,” what does that mean?

- Cash flow?

- Capacity?

- Brand perception?

- Or maybe the CEO’s cat that lives in the office?

A generic case-solving structure is an empty container. The interviewer has to do the work for you, which completely ruins the purpose of the whole thing.

People use generic templates because they’re easy to memorize. And yes, that's easy to understand.

But that's not what you actually want to show in the interview, right?

No prioritization (not choosing what matters)

One of the biggest giveaways of an underprepared candidate is the “framework dump”. It is when they list every possible branch of a structure with zero prioritization.

But you’re not supposed to investigate all of it. You’re supposed to decide which pieces matter first.

A strong candidate says something like:

“I’d like to explore X first because it seems most likely to drive the problem. But if that doesn’t explain the issue, we can move to Y next.”

Prioritization shows three things that any interviewer would value:

- Judgment,

- Intuition,

- Strategic thinking.

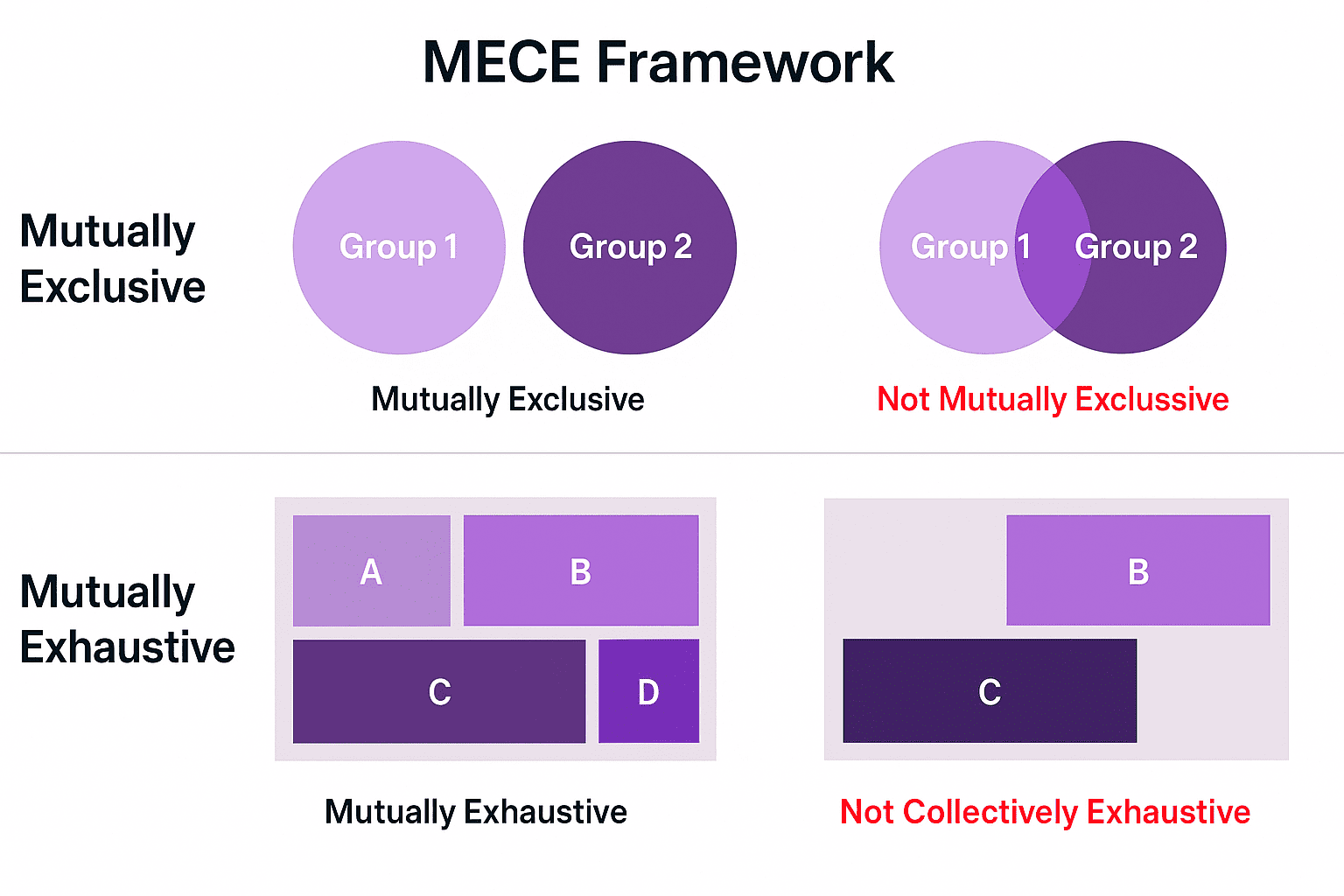

They are not MECE (mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive)

You might think that “MECE” has become cliché.

But when you ignore it, your structure becomes way too repetitive and sometimes even messy.

You end up mentioning the same idea twice under different labels:

- “Competition,”

- “Competitors,”

- “Market rivalry,” etc.

They are all the same thing (obviously).

Alternatively, you could split buckets in ways that overlap so much you can easily confuse not only the interviewer but also yourself.

A non-MECE structure leads to:

- Double counting,

- Contradictions,

- Gaps in logic,

- Circular explanations.

A MECE framework is just another way to make sure you are thinking clearly.

When your buckets overlap, your analysis gets tangled very, very fast.

The communication is weak

Sometimes the methodology is fine. And the real issue is delivery.

A candidate may have a solid structure but present it in a way that’s impossible to follow:

- Talking too fast,

- Listing items without explaining the logic,

- Jumping between buckets,

- Forgetting to signpost,

- Using vague wording.

A framework is a communication tool as much as an analytical one.

If the interviewer can’t follow your structure, it doesn’t matter how good it is. As simple as that.

Your case interview approach should guide the interviewer through your reasoning.

And you have to be crystal clear about what you’re doing and why.

Overly rigid structure without flexibility

There’s a noticeable moment in many interviews where the candidate’s structure technically “breaks.”

It’s when the interviewer gives new data that requires a pivot, and you... pretty much ignore it.

Some candidates adjust instantly, dropping a section, expanding another one, or even changing the whole approach.

Others are just sticking to what they have:

“…so, uh, before we get to that new information, I’d like to finish my analysis of distribution channels.” This attitude isn’t what you want.

A framework is not a cage, and you’re expected to be flexible and adjust promptly.

If you cling to your structure like it’s a script, you’re practically telling the interviewer you can’t adapt.

And as you know, it isn’t what they're looking for.

They don’t match how real businesses operate

Some approaches fail simply because they’re too academic.

Real businesses don’t think in perfectly neat buckets.

A retailer struggling with falling margins may not think in “customers, competitors, and company”. They think in:

- Store footprint,

- Assortment,

- Merchandising,

- Logistics,

- Labor costs,

- Pricing power, and tons of other more “tangible” characteristics.

If your framework doesn’t reflect how actual companies operate, it loses credibility (and common sense).

Interviewers can feel it when you’re speaking about things that are far from a particular business reality.

11 common case interview frameworks

Based on everything we’ve already talked about above, you understand that consulting templates aren’t something you “just memorize.”

They are tools. And each of them has a specific task.

- You don’t use a hammer when you need a wrench.

- And you don’t use a market entry framework when the client is asking how to decrease costs in their production process.

What you need to do is learn what each of them is and how you can apply them in real life.

This section breaks down the most common case interview frameworks used in consulting interviews. And shows you when (and why) you can apply them.

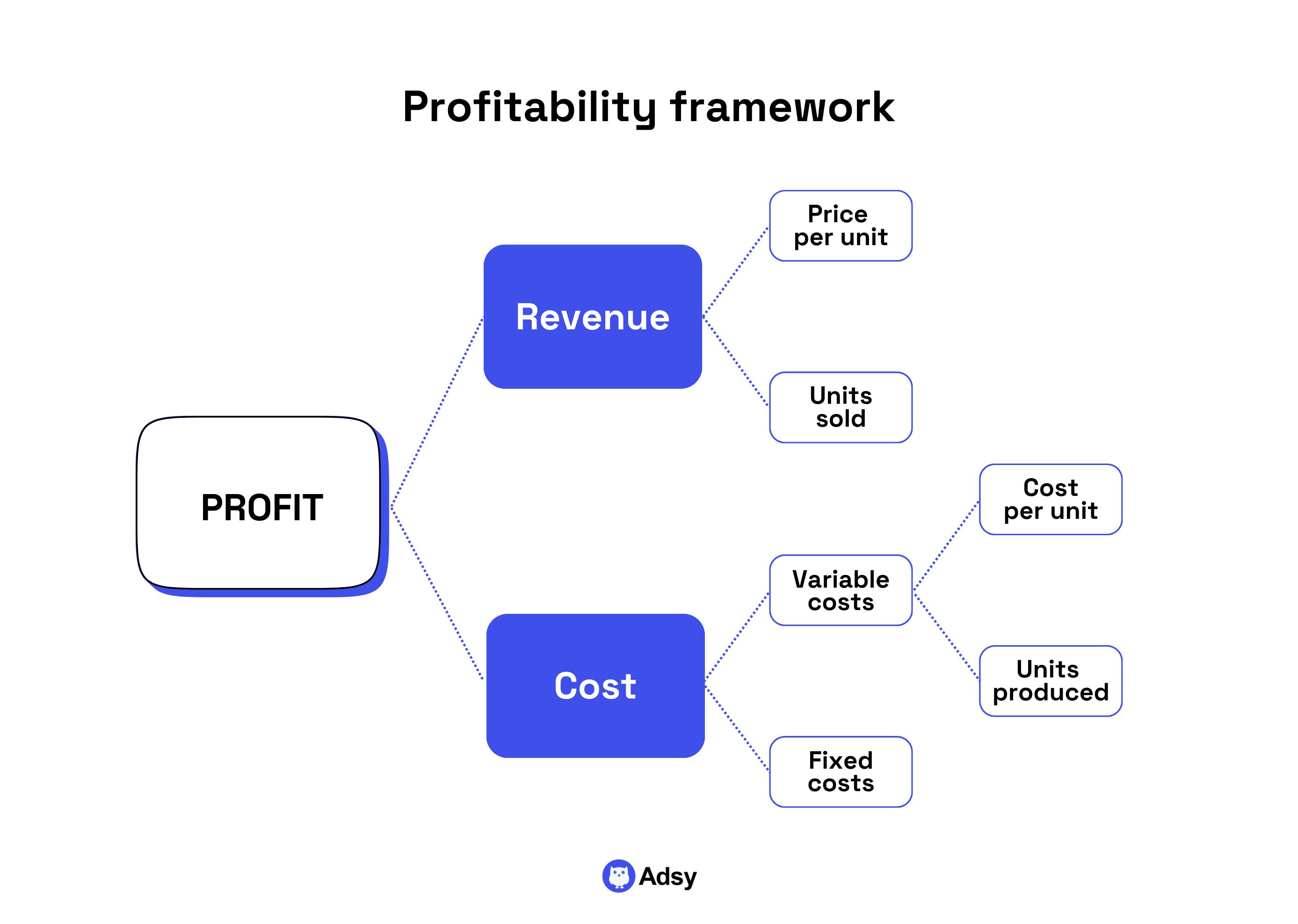

1. Profitability framework

If you walk into a case interview and the company’s profits are dropping, this is often your starting point.

But many candidates jump straight into cost-cutting suggestions and miss the big picture.

Here’s the simplest way to think about it: Profit = Revenue – Costs

Then, break it down:

Revenue

- Price,

- Volume,

- Pricing strategies (discounts, segmentation, perceived value),

- Mix (which products, which channels).

Costs

- Fixed costs (rent, salaries, overhead),

- Variable costs (materials, labor, logistics).

A good profitability case analysis approach makes you ask these questions:

- Is pricing on the same page with customer demand?

- Are there inefficiencies driving up variable costs?

- Is the company pursuing the wrong customers?

- Are certain distribution channels unprofitable?

When should you use it?

While there are many cases when this can be helpful, these are the main scenarios:

- When you need any financial explanation (margin drop, unprofitable services/products, etc.).

- When the performance is decreasing, and you need to find a reason for that.

- When you deal with strategic decisions (rethinking a service model, entering a new market, etc.).

- When you have contradictory finances (e.g., you see revenue or market growth, but the profits aren’t increasing).

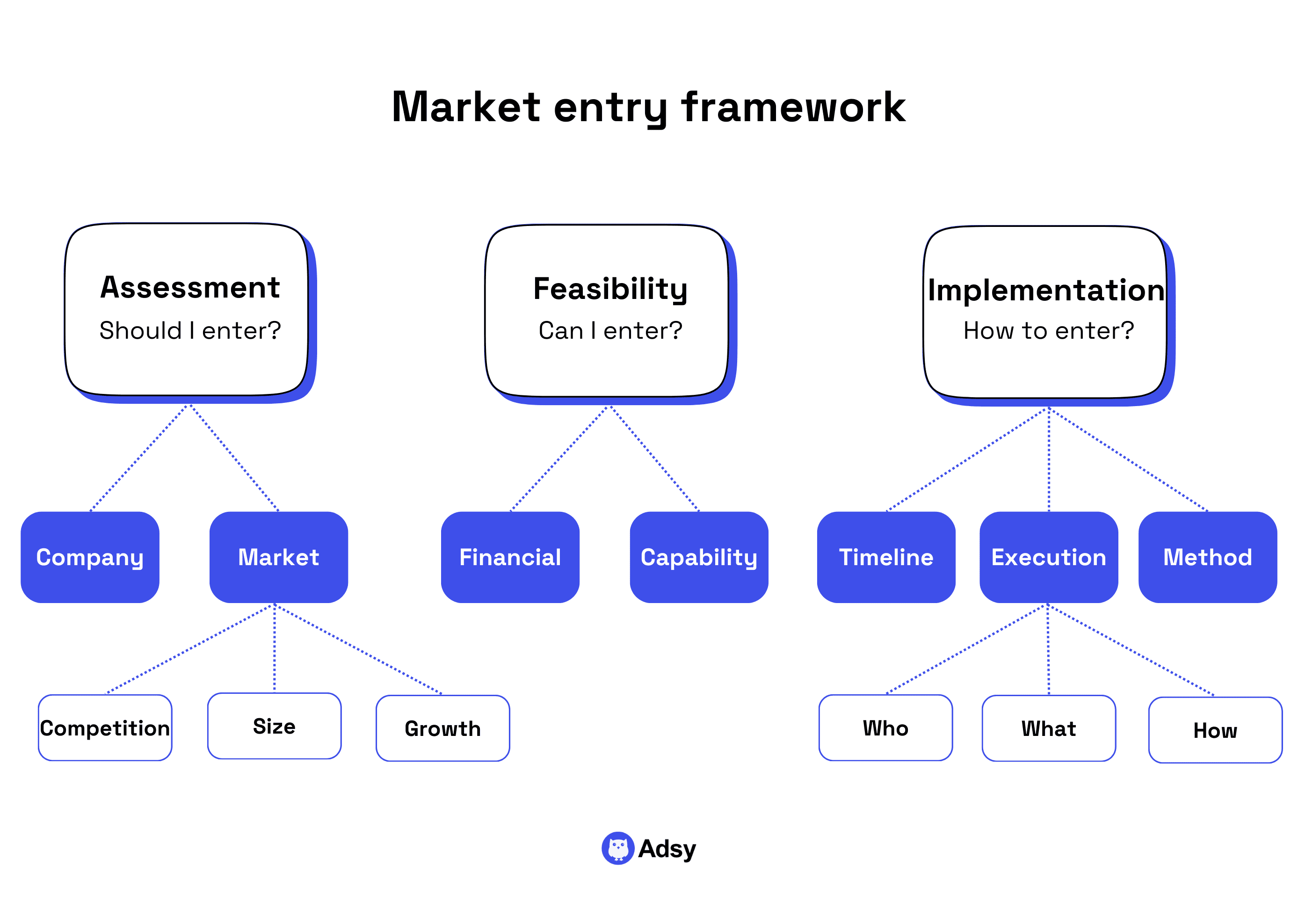

2. Market entry

One question you should ask yourself right away is this: Does it make strategic sense for the company to enter this space at all?

Always start with the company itself:

- Why are they even considering this move?

- Is the new market similar to what they already do, or is this a bold leap into unfamiliar territory?

Only then do you look outward: at customers, competitors, and regulatory quirks that might make entry surprisingly harder or unexpectedly easier.

Never try to “cover everything.”

Strong candidates show that they understand one thing clearly: entry decisions are strategic bets.

When should you use it?

- A company wants to expand geographically or into a new product category.

- A client is deciding between building internally, partnering, or acquiring.

- The interviewer hints at a “growth opportunity,” but the path is unclear.

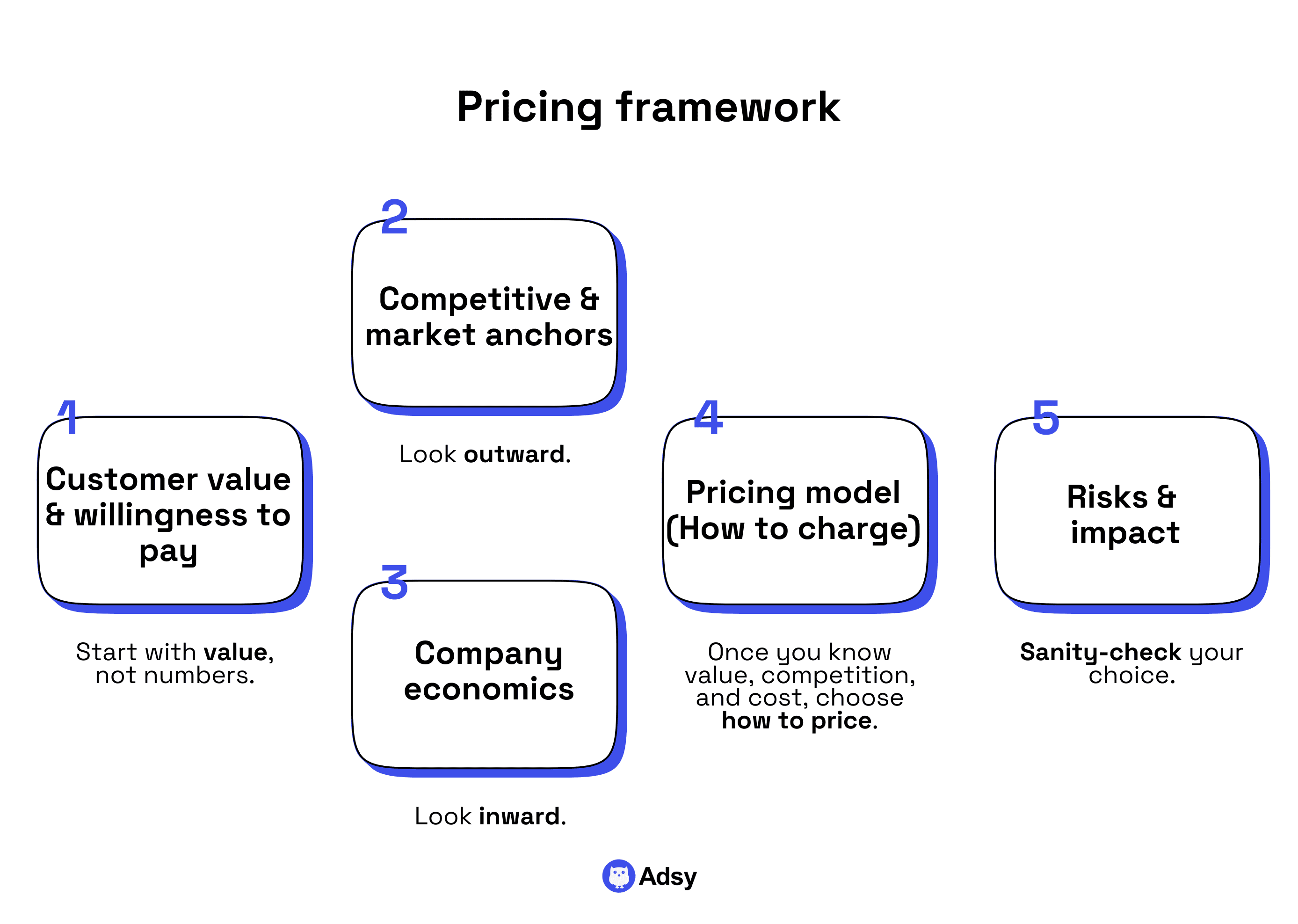

3. Pricing: The most misunderstood model

Many candidates treat pricing like it’s the simplest framework. Cost + margin, customer willingness, and competitor benchmarks. But pricing is not a math exercise. At all.

Essentially, it’s psychology and positioning wrapped inside business constraints.

You start by understanding what drives value in the eyes of the customer. What are they actually paying for? Faster delivery? Prestige? Security? Stability?

Once you understand value, the pricing levers suddenly make sense.

- Maybe you use tiering.

- Maybe a subscription model.

- Maybe bundling or unbundling.

One thing you shouldn't do is go straight to numbers. What you would rather do is talk about behavior.

But it isn’t just value. Overall, the pricing analysis comes down to these elements:

- Customer value and their willingness to pay

- Competitors and market trends

- Company economics and margins

- Pricing model options

- Risks and implementation

When should you use it?

- The client is launching something new and has no idea what to charge.

- There’s a margin problem rooted in weak monetization, not costs.

- Competition is shifting the price anchors in the market.

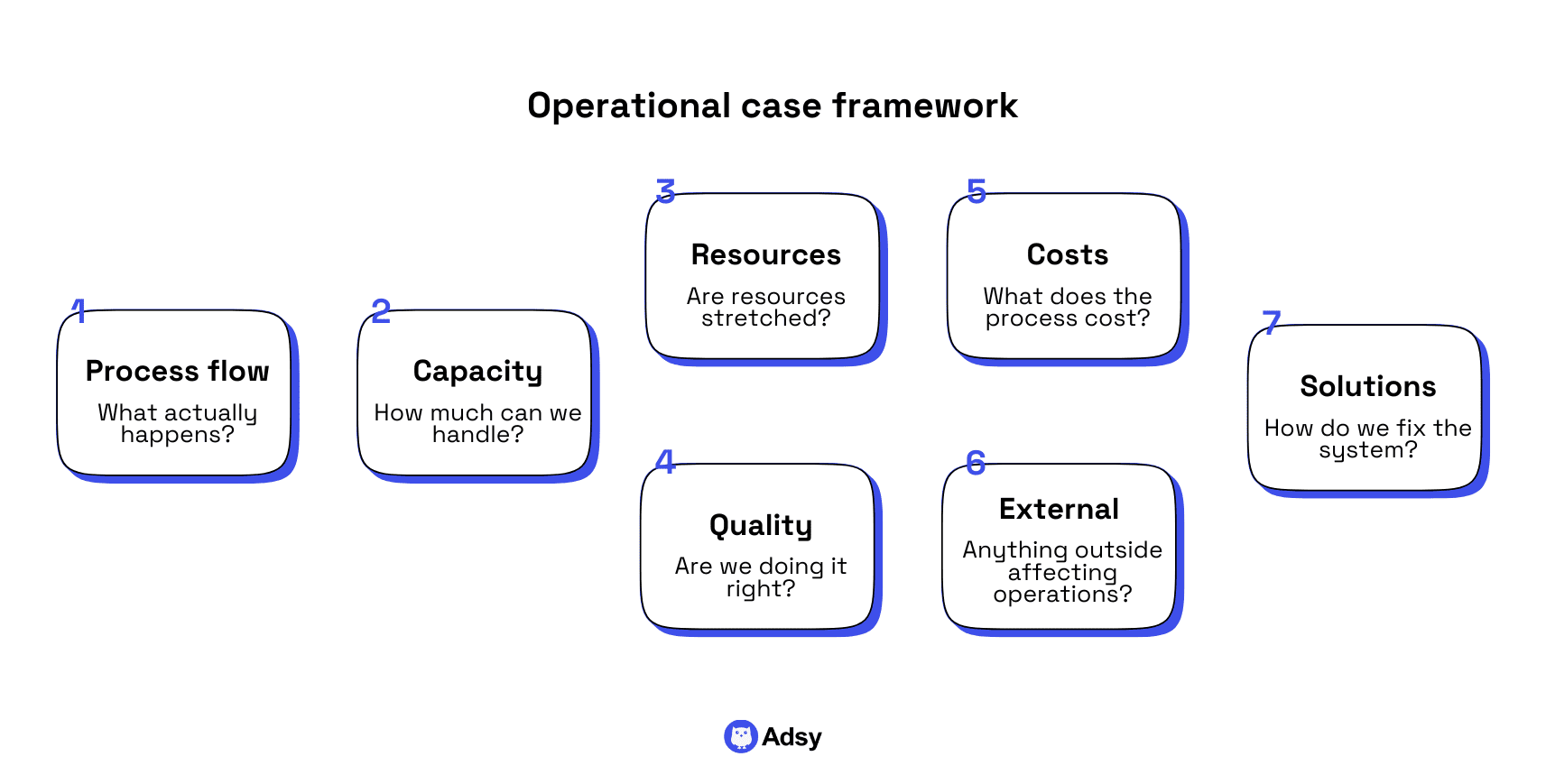

4. Operations: When the problem lives inside the machine

Operational frameworks only sound “technical” if you’ve never used them.

In reality, operational cases are about finding the point where the system slows down and deciding what to do next.

Maybe you need a redesign, some automation, or simply better/different processes.

This one often comes into play when a client has quality failures or supply chain volatility. Sometimes, when they simply want to do something “faster, cheaper, or at higher capacity.”

Whatever you do, don't memorize operational terms here. Instead, listen, sketch the flow, identify the stress points, and ask grounded questions.

When should you use it?

- There is a manufacturing, logistics, service delivery, or supply chain inefficiency.

- The case mentions delays, defects, idle capacity, or shortages.

- The client needs to scale something operationally.

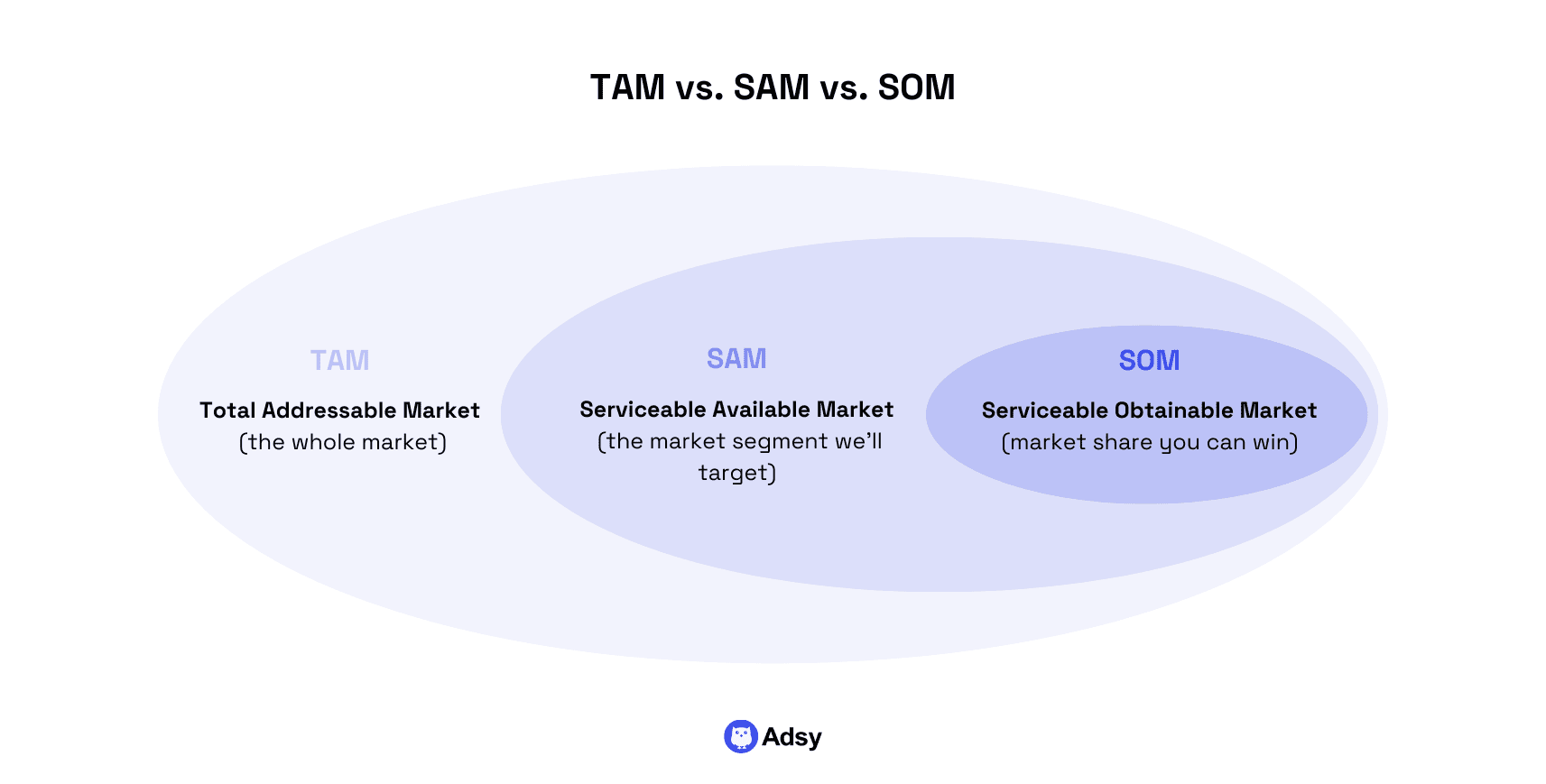

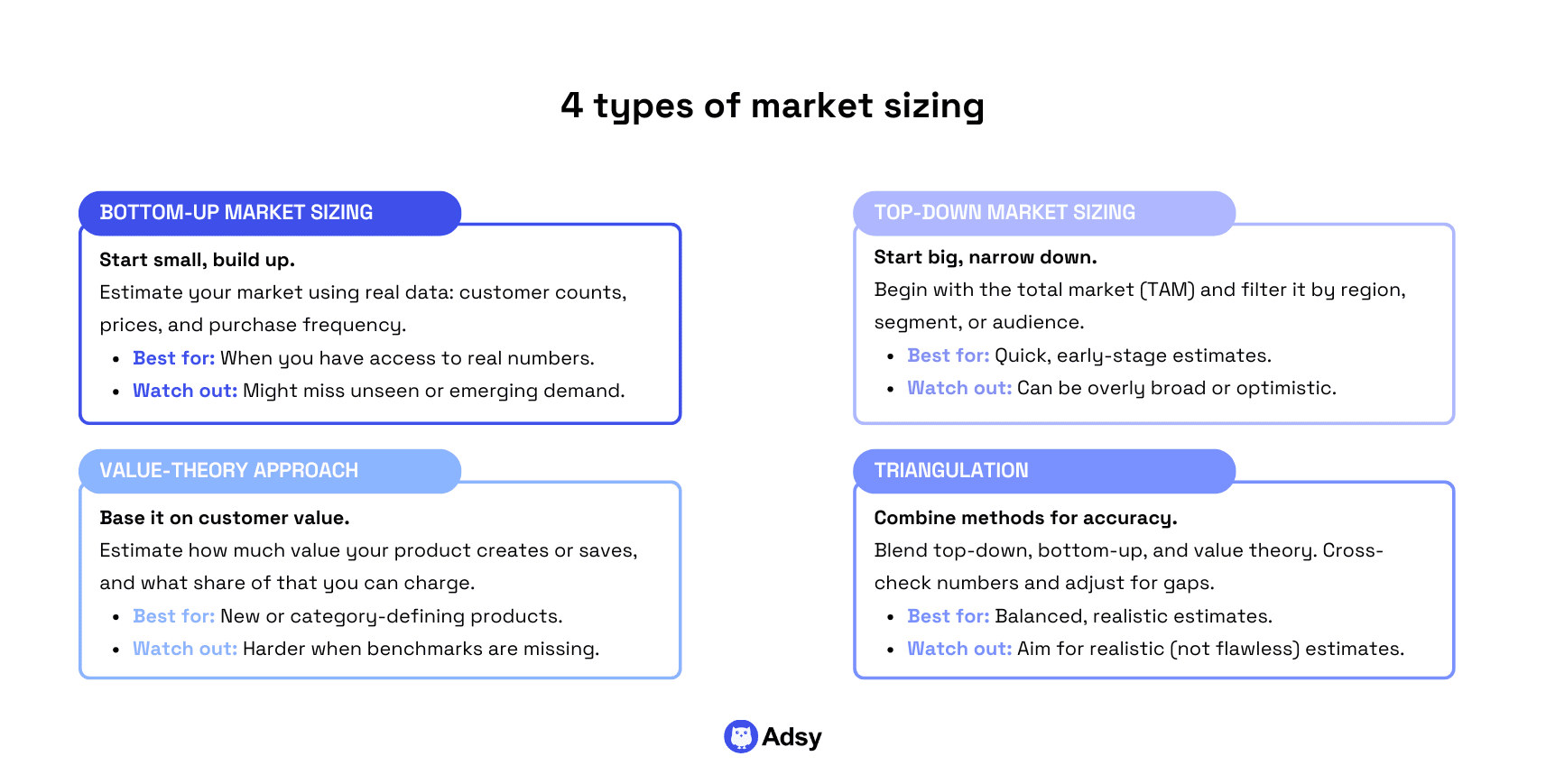

5. Market sizing: Your ability to think from zero

Market sizing has only one purpose: showing that you can think clearly without external data. That’s it.

There's no reason to rush through it. Instead, explain your reasoning and show an interviewer how you can handle a “messy” idea.

It isn’t about giving a “perfect” number. It’s about proving that you can operate under pressure and in uncertainty.

How can you approach it?

- Look at the data you have.

- Decide what type of market sizing makes the most sense (top-down, bottom-up, etc.).

- Then build from there.

Break the problem into simple components, make transparent assumptions, multiply through, and sanity-check the final answer.

The structure doesn’t need to be fancy. It just needs to be clear.

After all, you’re showing you can be wrong intelligently rather than confidently incorrect.

When should you use it?

- An interviewer gives you a quick estimation problem.

- You need to size the demand inside a larger case.

- You’re testing whether a business idea has enough market potential at all.

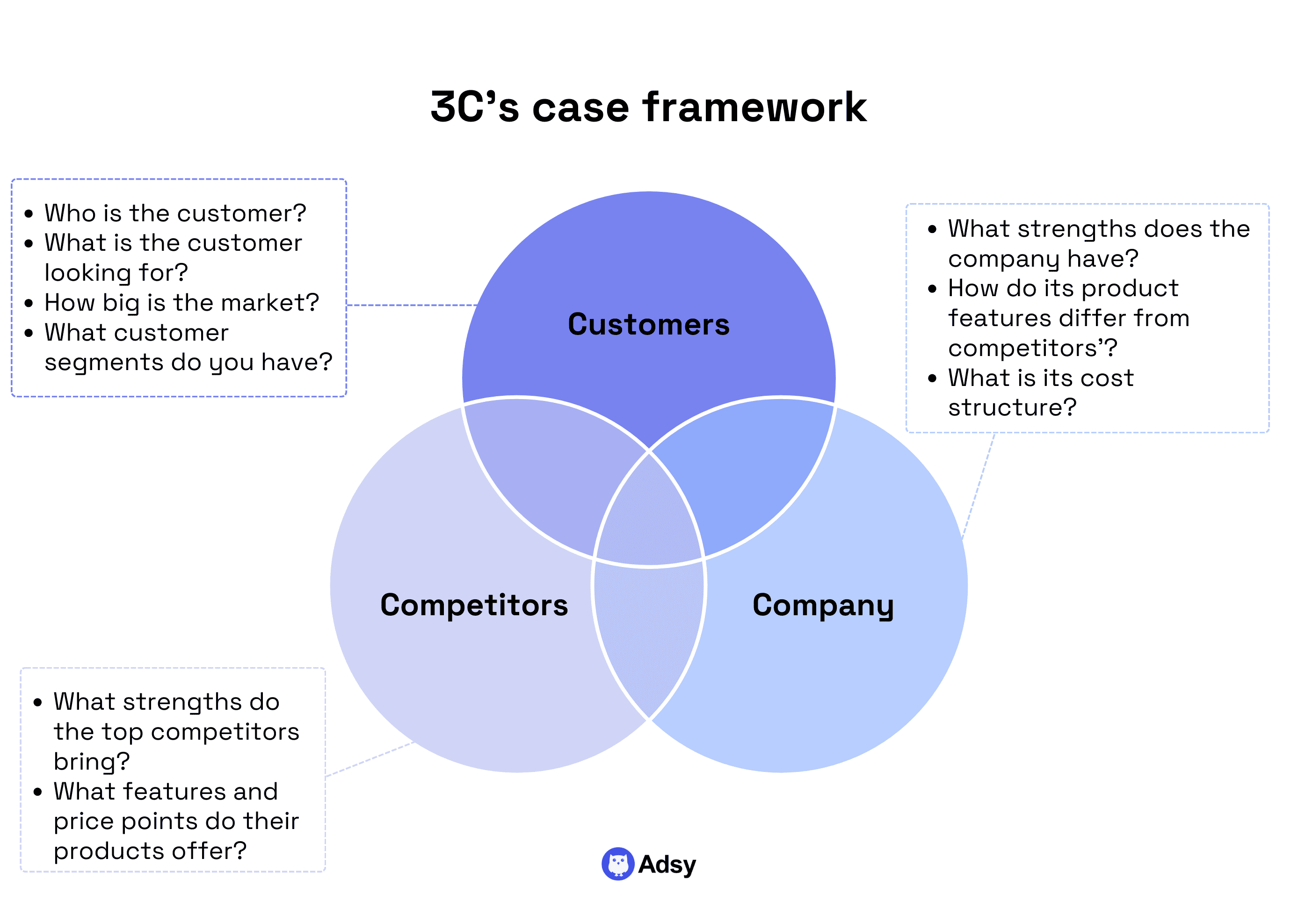

6. 3C’s: The most natural “business sense” approach

3C’s means company, customers, competition.

It is the business situation methodology that consultants rely on when they want to quickly understand where they should be heading.

It’s flexible, and it works for almost everything.

Basically, it forces you to look at a problem from three angles at the same time:

- Internal ability,

- External demand,

- Competitive pressure.

When should you use it?

In a case interview, it’s most useful when:

- The problem is ambiguous.

- The business challenge is broad.

- There’s no obvious “type” of case (not clearly profitability, not clearly market entry).

The best approach when using 3C’s is to make it a clarifying step.

You don't have to force it.

It would be a good thing just to ask: “Before we go deeper, what is happening with the company itself, the customers they serve, and the competitive landscape around them?”

Likely, this approach won’t be your last step. But at the discovery stage, it could actually be helpful if you feel like you lack some insights.

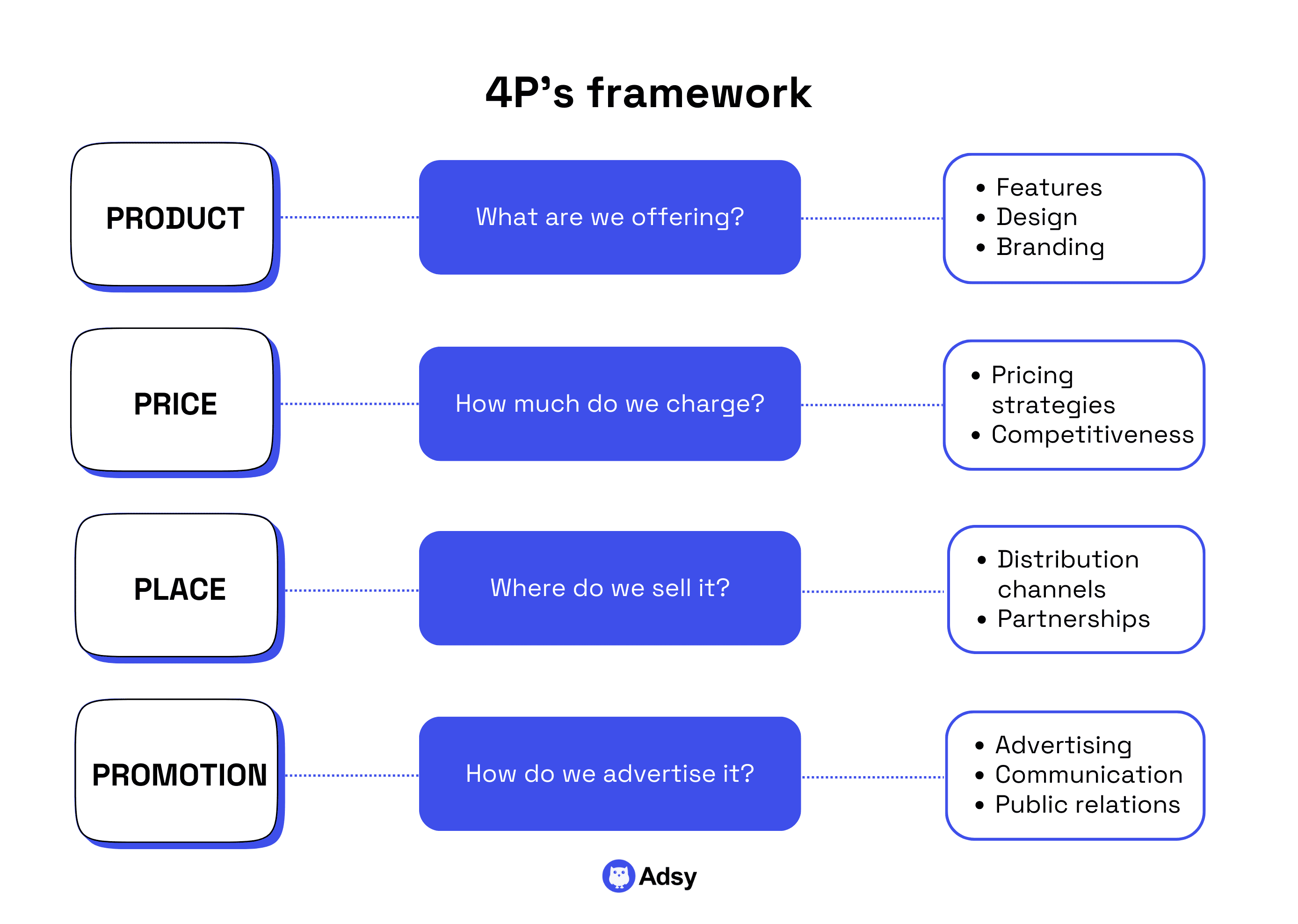

7. 4P’s: When marketing is the heart of the case

4P’s (product, price, place, promotion) is about understanding how to position and distribute an offering.

It’s another “classic.” But its effectiveness will depend on how you treat it.

Essentially, the 4P’s isn’t about analyzing the four Ps. It’s about thinking through customer experience.

You want to ask questions like:

- Is the product solving the right problem?

- Is the pricing correlating with value?

- Are we selling it where our customers actually look for it? Do they need it?

- Does anyone even know it exists?

When should you use it?

- A client has a product that isn’t performing.

- A new launch needs a go-to-market plan.

- The interviewer hints at “weak uptake,” “poor adoption,” or “low awareness.”

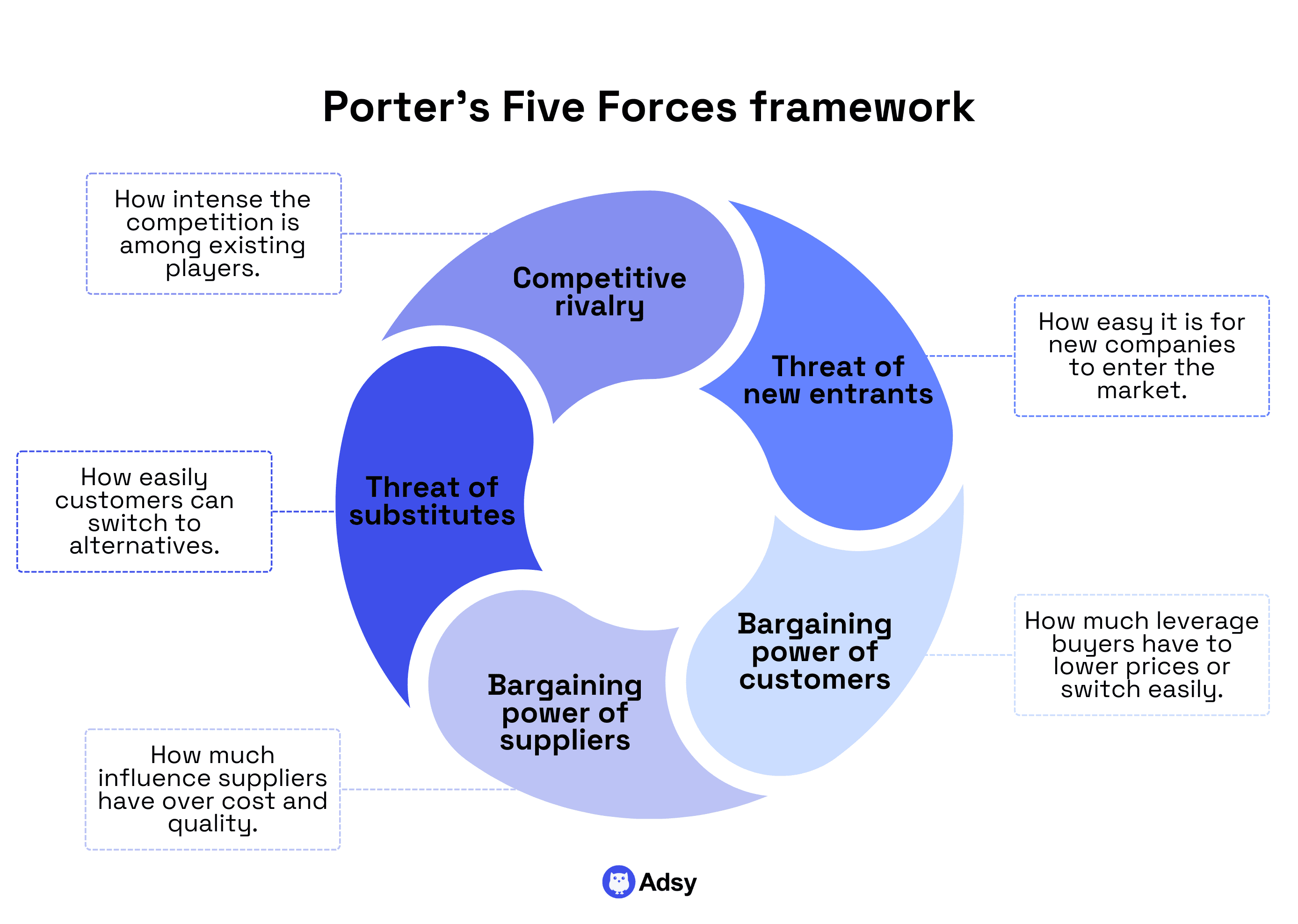

8. Porter’s Five Forces: The industry reality check

From 3s and 4s, we've made it to 5. Porter’s Five Forces only works if you use it conversationally.

If you recite all five forces like a checklist, you’ll simply sound like ChatGPT.

But if you treat the model as a way to think about pressure points in an industry, you’ll sound exactly right.

Here, you’re basically asking:

- How much power do customers and suppliers have?

- How fierce is the competition?

- How easy is it for new players to enter?

- Are substitutes waiting to steal demand?

This case interview approach is your go-to when the interviewer is asking something at the industry level.

But when the questions are at the company level, you typically don't have to apply it. Still, always remember to consider all the elements of your problem and lead with reasoning.

When should you use it?

- The client wants to enter a new industry.

- A particular sector is consolidating or fragmenting.

- The dynamics of the competitive environment matter more than internal factors.

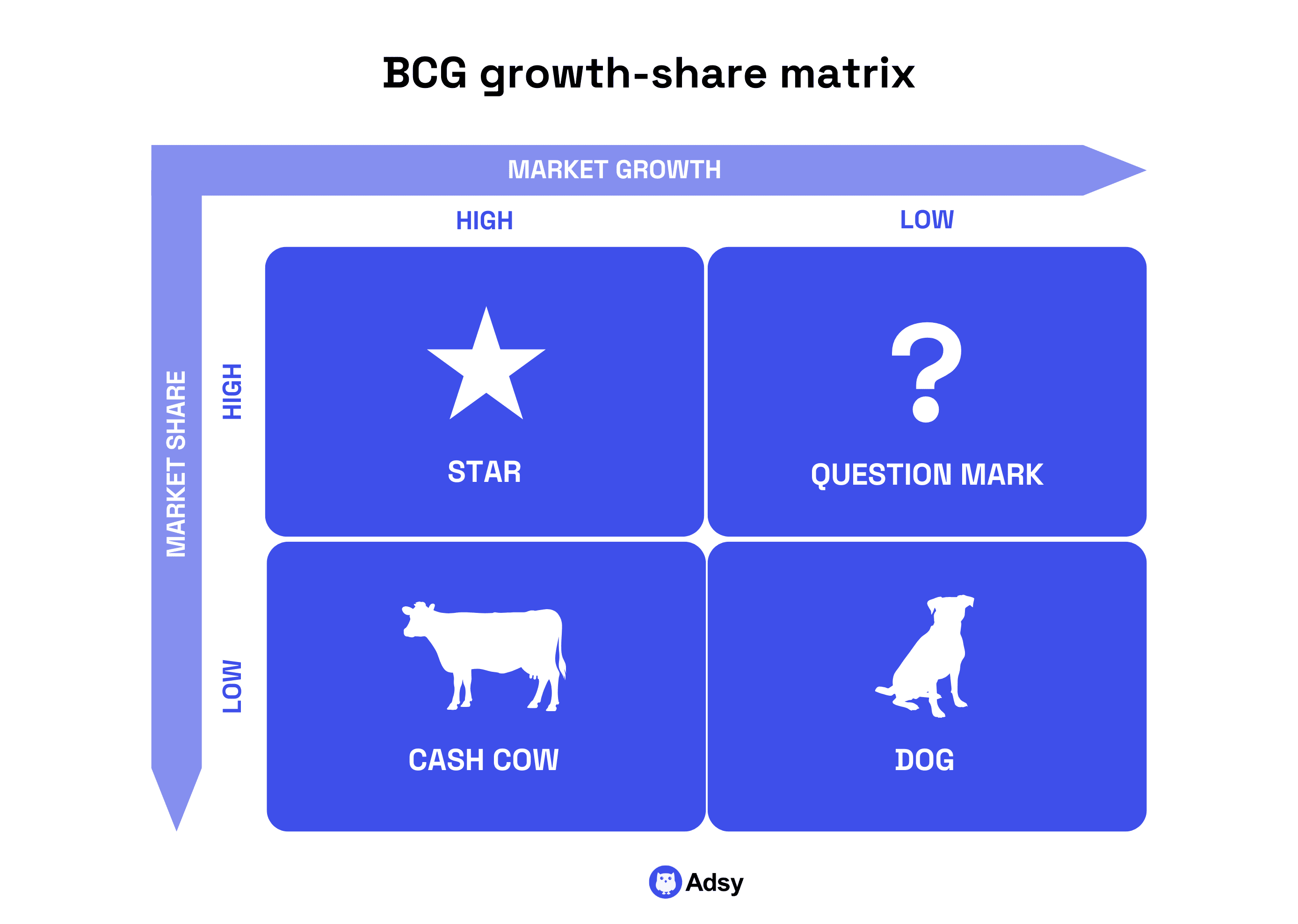

9. BCG Matrix: A portfolio talking tool

The BCG Growth-Share Matrix is a way of thinking about how a company should allocate resources across multiple businesses or product lines:

- Stars are your best bets for future growth.

- Cash cows are profitable, but it isn’t something you overinvest in since the growth is low.

- Question marks could become your “stars,” but could also fail (if you’re looking for some riskier and less obvious bets, this is it).

- Dogs are things you want to avoid since both the profit and growth are low.

Think of it as a simple way to answer: “Which parts of the business deserve our attention and resources?”

Still, it is just 4 boxes. So, of course, like almost any other matrix, it can’t give you everything you need.

That’s why it is not something you would normally use in isolation. Most consultants would often combine it with a deeper analysis.

In any case, it is very helpful when you need more structure while evaluating market growth and share.

A good candidate uses the matrix to guide decisions.

So, these would be the logical questions to ask:

- What do we scale aggressively?

- What do we optimize for steady cash flow?

- What do we experiment with?

- What do we let go?

When should you use it?

- The client operates a multi-product or multi-business portfolio.

- There’s a decision about where to invest.

- Growth and share differences create internal tension.

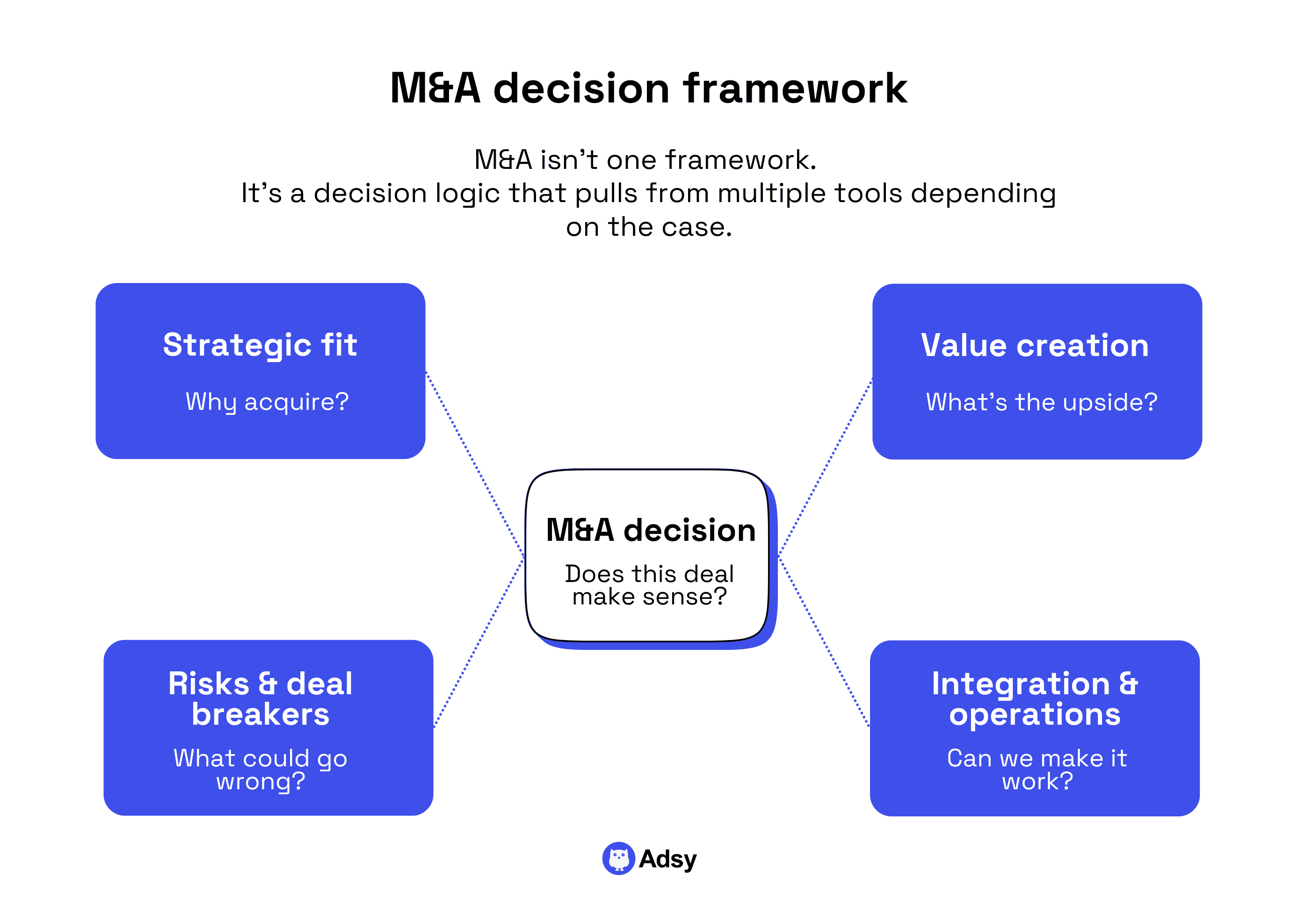

10. M&A: When things get specialized

M&A cases are their own category because they blend multiple frameworks into one question: “Does this acquisition make sense strategically and operationally?”

Typically, you would have to conduct a deep analysis that covers:

- Strategic elements. Why would you need this deal in the first place?

- Value. What realistic benefits can you expect?

- Potential integration issues. Are you a good fit together?

- Any risks. Is there something major that could kill the deal?

You can also assess some alternative scenarios as the fifth element. This might mean a partnership instead of an acquisition. Or you might consider building it in-house. Sometimes, you’d just decide that the whole idea isn’t worth the effort.

When should you use it?

- The case explicitly involves an acquisition, merger, or partnership.

- The client is evaluating buying/building/partnering.

- There’s a major expansion that requires external capabilities or assets.

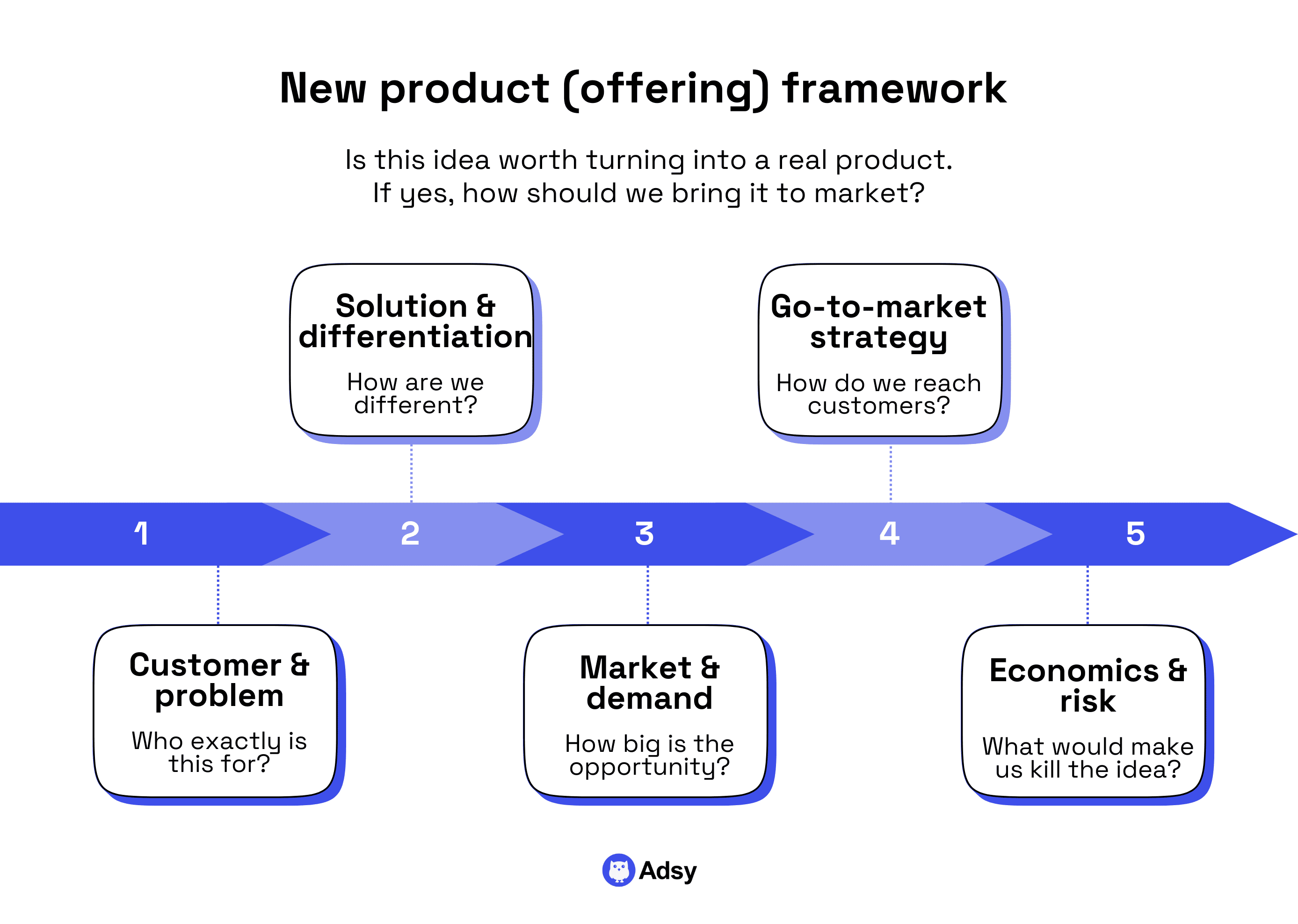

11. New product or offering: When you need product-market clarity

New product cases operate similarly to the general ones but focus more on customer needs, product fit, and go-to-market elements.

Candidates who perform well here often think like product managers:

- Who is this for?

- What problem does it solve?

- How do we prototype, launch, test, and scale?

So, long story short, you have to concentrate on whether this new idea has a chance of succeeding as a product. Normally, you would assess everything from problem and differentiation to demand and risks.

Again, there is no strict framework, but rather a complex system of questions you have to address.

When should you use it?

- The business is creating or launching something new.

- The interviewer hints at “testing demand,” “product fit,” or “go-to-market.”

- You need to assess whether an idea has real potential before investing.

|

Framework |

What it helps to do |

Core idea |

Best for |

|

Profitability |

Diagnose performance problems |

Break profit into revenue & cost drivers |

Declining margins, losses, efficiency problems |

|

Market entry |

Evaluate if entering a new market makes sense |

Align internal capabilities with external opportunity |

New geographies, new segments, strategic expansion |

|

Pricing |

Understand how to charge for value |

Combine customer psychology, market anchors, and cost logic |

Monetization, new products, margin fixes |

|

Operations |

Fix internal bottlenecks |

Map processes, find constraints, redesign flow |

Production, logistics, service delivery |

|

Market sizing |

Estimate demand from scratch |

Break a market into logical components |

Quick estimates, feasibility testing |

|

3C’s |

Make sense of messy business situations |

Look at company, customers, and competition |

Ambiguous cases, diagnostic conversations |

|

4 C’s |

Build or fix go-to-market strategies |

Product, price, distribution, and awareness |

Launches, marketing challenges, weak adoption |

|

Porter's five forces |

Read an industry’s pressure points |

Analyze power, rivalry, entry, substitutes |

Industry-level questions, strategic landscape |

|

BCG matrix |

Allocate resources across a portfolio |

Growth vs. share informs investment |

Multi-product companies, prioritization |

|

M&A matrix |

Evaluate merging or partnering |

Strategic fit, financial impact, and integration risks |

Acquisitions, mergers, partnerships, build-vs-buy decisions. |

|

New product or offering case |

Assess product-market fit and plan how to launch successfully |

Understand customer needs and map the go-to-market path |

New features, product launches, testing early-stage ideas. |

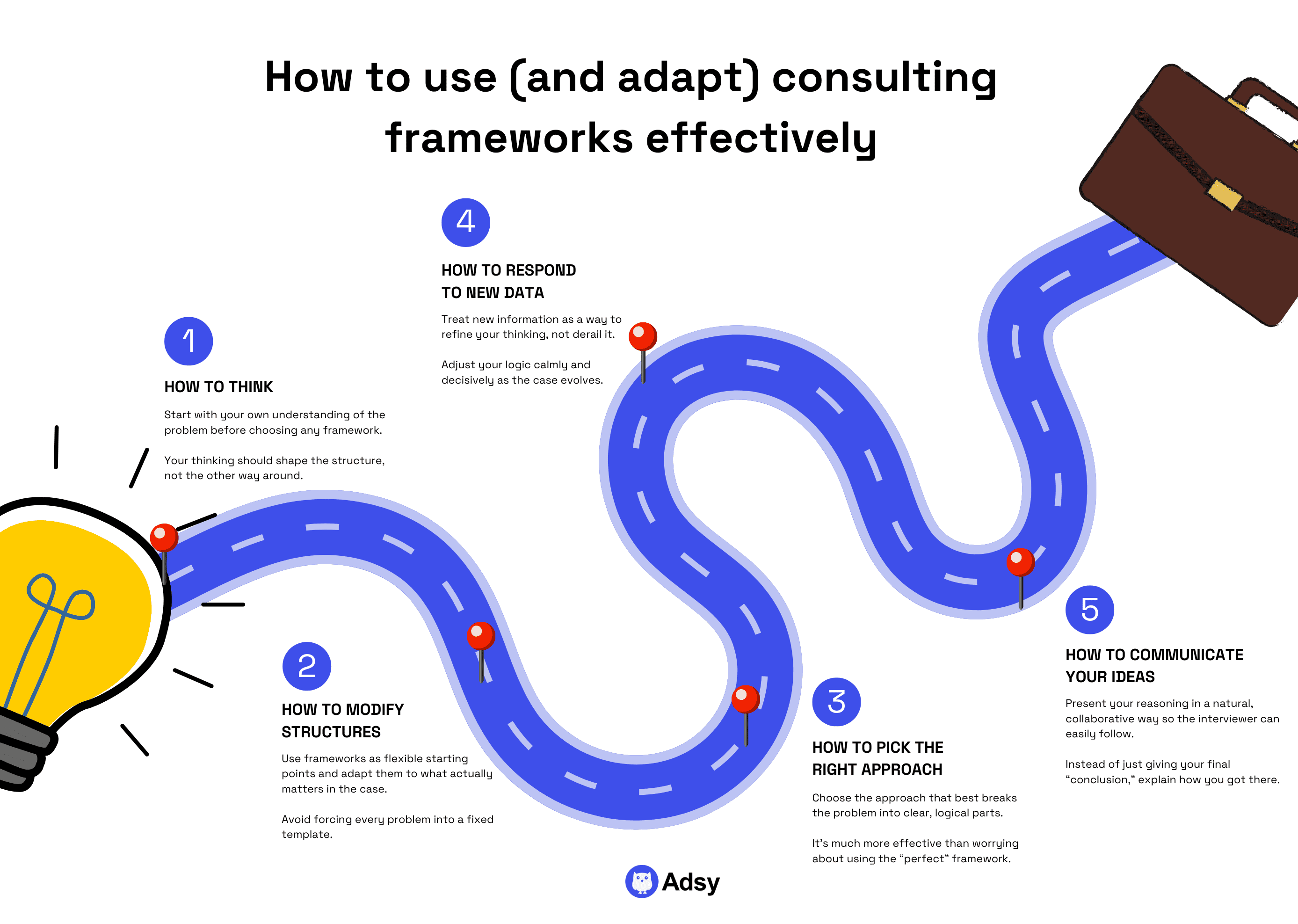

How to use (and adapt) consulting frameworks effectively

If you’ve made it this far, you already understand the approaches themselves.

Now comes the part that separates people who “know frameworks” from people who actually think with them.

This is what interviewers really watch for: not whether you memorized anything, but whether you can take a loose structure and adapt it on the fly.

Because you need to integrate new information and communicate as if you’re discovering the logic in real time.

The irony is that people who cling most tightly to templates usually struggle the most in case interviews.

They walk in terrified of going off-script and try to force-fit everything into a neat diagram. Even when the problem clearly doesn’t match the boundaries.

So, let’s walk through the hardest part: how to think, adapt, and communicate using frameworks the way they were meant to be used.

Step 1: How to think (before you even touch a template)

The first mental shift you need is actually quite simple: a template is not a starting point.

Your thinking is the starting point. Frameworks just help you shape it.

When you hear a case prompt, don’t rush to the “correct structure” because there isn’t one. Just slow down and ask yourself the same questions a consultant would ask in a real project kickoff:

- What is the core question here?

- What does the client actually care about?

- What’s the most likely source of the problem?

- Do I already have a hypothesis?

- What are the broad categories I need to investigate?

Only after you’ve had that initial internal conversation does a framework begin to matter.

Usually, candidates sound less convincing because they skip this mental moment.

They move straight into “I will structure my thinking using X approach”. All without showing that they’ve actually heard the problem or reflected on it.

Step 2: How to modify structures so they fit your case

Unfortunately, most real cases don’t fit into any single consulting framework. Why? Mainly, because the reality is too messy:

- Markets overlap with operations.

- Pricing connects to strategy.

- Competition blends with customer behavior.

If you try to force the world into a rigid formula, you’ll struggle.

Here’s the useful mindset:

Every case interview structure is a starting skeleton. You add muscles, nerves, and skin depending on the case.

For example:

- Profitability usually begins with revenue and cost, but the deeper levels depend on the business model. A subscription business breaks down differently from a retailer or a manufacturer.

- Market entry starts with attractiveness and capabilities. But if the client is a startup, the capability question dominates everything. If the client is a global conglomerate, scale and speed matter more than “fit.”

- Porter’s Five Forces is great for understanding an industry, but sometimes only two forces actually drive the problem. You don’t need to talk about all five unless all five matter.

Do not say something like:

“I’ll analyze customers, competitors, and the company.”

Instead, you might say:

“Before I choose a direction, I’d like to understand three things. What customers need, who else is serving those needs, and whether our client is well-positioned to compete.”

Adaptation is not a trick: it’s simply choosing what's relevant. If a part of a traditional template doesn’t matter in this case, leave it out.

Step 3: How to pick the right approach

One of the biggest reasons candidates cling to memorization is fear. And it is the fear of picking the wrong framework.

But here’s something interviewers won’t always say out loud: most of the time, more than one approach works well as long as you can use it logically.

The right methodology is the one that helps you break the problem into clear, MECE components. That's it.

Here’s the selection logic real consultants subconsciously use:

- If a business is underperforming: start with profitability or a diagnostic tree.

- If a business wants to grow: consider market entry, pricing, customer analysis, or product strategy.

- If a business wants to enter a new space: look at attractiveness, competitive dynamics, and capability fit.

- If the problem is ambiguous: start with 3C’s or a custom issue tree and narrow from there.

- If it’s about how the industry behaves: Porter’s Five Forces gives you clarity fast.

- If there are multiple products or business lines: bring in portfolio logic (like BCG).

- If it's new data, new products, or acquisitions: build a hybrid structure tailored to the context.

None of these should be treated as rules, because they are not. They’re actually patterns.

If you do this well, the interviewer won’t think about the framework’s name. They’ll just see that your thinking is clean and reasonable.

Step 4: How to respond to new data

That's probably the most important part, right?

Most people know their case interview templates. What they struggle with is flexibility. Why? Because the moment the interviewer gives them a surprising piece of information, they freeze.

This usually happens because they’re too attached to the structure they committed to earlier.

But look, in the end, it is all about the right mindset.

The right mindset would be realizing that new information doesn’t break your structure. It refines your understanding.

Here's how you can organize everything when you hear something unexpected:

- Pause first. Even a single breath makes you sound calmer and more thoughtful.

- Acknowledge that this information is helpful.

- Interpret it. In other words, explain what it means for the logic of the case.

- Use it decisively. Either adjust your path or confirm your hypothesis.

Do not say something like:

“Okay, so I guess that means… let me adjust my framework…”

Try:

“That changes things. If 80% of demand is concentrated in one segment, it makes sense to focus our analysis there instead of treating all customers equally.”

Essentially, flexibility is responsiveness. And it is one of the strongest signals that you are ready for the job.

Step 5: How to communicate your ideas properly

You can have perfect logic and still fail if the interviewer can’t follow you.

Communication is the delivery system for your thinking, so you have to work on this one a lot.

Good case communication has a few core traits:

- Even if your thoughts are structured, they need to flow. Interviewers should feel like they’re listening to a natural explanation. Do not recite some random memorized content.

- Speak as if you’re solving the problem together. This might help you feel less stressed. You are not a student or a teacher here. Imagine like you’re explaining your points to a colleague.

- Make your tone collaborative. Walk your interviewer through your reasoning, like you’re thinking out loud.

Give more context to show your actual thinking process.

Here is an example:

Not:

“Variable costs are rising because procurement prices increased.”

But:

“One pattern jumps out: most of the margin pressure is coming from rising variable costs. So, procurement prices seem to be the biggest driver.”

Yes, it is a small change, but it has a huge effect. Why? Because you transition thoughtfully.

Still, don't go for dramatic transitions either. Use natural, normal language.

When you finish one part of the analysis, briefly summarize what it means and connect it to the next step. Interviewers love that because it shows clear logic.

Conclusion

By now, it should be obvious: frameworks are not the goal. They’re nothing but a support structure. The real goal is structured thinking, adaptability, and clear communication.

When interviewers say they’re looking for “structured candidates,” they don’t mean “people who memorize structures.”

They mean people who can take an unfamiliar business problem, organize it intelligently, and adjust when the world changes. Yes, and bring others along through confident communication.

All trademarks, logos, images, and materials are the property of their respective rights holders.

They are used solely for informational, analytical, and review purposes in accordance with applicable copyright law.